Respiratory infections, vaccinations and your heart

What are respiratory infections?

Respiratory infections are a group of conditions where an infection affects your lungs, making it difficult for you to breathe properly.

What causes respiratory infections?

Respiratory infections are most commonly caused by a virus, but they can also be caused by bacteria. In Australia, the viruses that often cause respiratory infections are rhinoviruses (‘common cold’), influenza viruses (‘the flu’), respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), and severe acute respiratory coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2, or ‘COVID-19’).

Respiratory infections are very common and can be caught by people of any age. In otherwise healthy people, the symptoms are generally mild, and the infection will clear within a week or so. However, in some rare cases, or in people who are frail or have other health conditions they can become more serious.

What is the link between respiratory infections and cardiovascular disease?

Respiratory infections and cardiovascular disease (CVD) are linked in three main ways:

- People with CVD are more likely catch a respiratory infection, and more likely to have serious complications from an infection. This includes a higher risk of needing to go to hospital, and in some cases, of dying. For example, people with CVD can be 10 to 20 times more likely to catch RSV and up to 4 times more likely to end up in hospital with the infection.

Respiratory infections can lead to CVD. Viruses can cause inflammation in your body, placing strain on your heart which can lead to heart failure or an abnormal heartbeat. Viruses can also cause plaque (a fatty build up) in your blood vessels to be less stable, and this can cause a blockage and possible heart attack or stroke. Your chance of having a heart attack in the week following an infection is six times higher following flu, up to 11 times higher following RSV and between two to eight times higher following COVID-19.

Respiratory infections and CVD share a number of common risk factors. For example, smoking increases your risk of catching a respiratory infection and increases your risk of developing CVD or having a heart event like a heart attack. Other shared risk factors include overweight and obesity, being physically inactive, and eating an unhealthy diet.

Can you prevent respiratory infections?

If you are living with CVD, it is important to be extra careful about preventing a serious respiratory infection. The most effective way to prevent serious respiratory infections is by having a vaccination, where available.

Vaccines are not yet available for all respiratory infections, but vaccines are available for:

Coronavirus/COVID-19

- COVID-19 vaccinations can reduce how sick you get and your risk of death from a COVID-19 infection. In particular, they can reduce your risk of developing heart failure, heart attack and stroke after having a COVID-19 infection.

- COVID-19 vaccines are recommended for everyone over the age of 18, and in people with existing health conditions, from 6 months.

- If you have a heart condition, your GP may recommend additional doses or boosters of a COVID-19 vaccine.

- Currently, COVID-19 vaccinations are free for everyone in Australia.

Influenza/the flu

- Influenza vaccines can reduce your risk of becoming very ill with the flu. Specifically, in people with CVD, a flu vaccine can reduce your risk of being hospitalised with the flu and of having a heart event for up to a year. Flu vaccinations can also reduce the risk of a heart event in people without pre-existing CVD.

- Influenza vaccination is recommended for everyone 6 months and older.

- A dose of influenza vaccine is required every year. This is particularly important for people with heart conditions, and First Nations peoples, who are at higher risk of becoming very ill from an influenza infection.

- People with heart disease, people 65 years and over and First Nations peoples can receive a free flu shot every year under the National Immunisation Program.

RSV

- RSV vaccinations can help prevent you becoming very ill with RSV. Your risk of having a heart attack and heart failure after an infection is also reduced for up to a year by having an RSV vaccination.

- RSV vaccinations are recommended for people aged 75 years and older, or First Nations peoples 60 years and older; pregnant people; and people at high risk of developing severe RSV.

- RSV vaccines are not currently covered under the National Immunisation Program or Medicare, but they can be purchased with a prescription from your GP.

Other ways that you can help prevent respiratory infections include:

- Wash your hands often with soap and water.

- Cover your coughs and sneezes with your elbow or a tissue.

- Use alcohol-based sanitisers to keep surfaces you use clean.

- Avoid touching your eyes nose and mouth.

- If you are sick, or someone you are around someone who is sick, practice physical distancing to limit close contact.

You can also help to reduce your risk of experiencing heart events from a respiratory infection by looking after your heart health. Some things you can do to take care of your heart are:

Respiratory infection, vaccination and cardiovascular disease FAQs

Are respiratory infections really that dangerous?

In otherwise healthy people, respiratory infections usually involve mild symptoms such as a sore throat, runny nose, cough and tiredness, which will pass within a week or two.

Sometimes though, people experience more serious infections that can need hospitalisation and even result in a person dying. People living with CVD are more likely to catch this more serious type of infection.

What are vaccines?

Vaccines are like a type of ‘practice run’ for your body. They introduce a small, non-infectious part of a bacteria or virus so that your body can build an immune response, which it remembers. This means that it is ready to go with a quicker response if you ever become exposed to that bacteria or virus again.

There are different types of vaccines – some of them contain bacteria or viruses that have been killed or weakened, or just a small piece of them; some have the toxins that are made by bacteria; while others contain instructions that tell your cells to make these small pieces themselves (mRNA vaccines). Vaccines also contain other substances called adjuvants. These help the vaccine be more effective by enhancing the immune response, or reducing the number of doses needed of a vaccine.

Are vaccines safe?

Yes, vaccines are safe. In Australia, vaccines are extensively tested to make sure they are safe and work as they are supposed to before being approved for use.

Can a vaccine make me sick?

After you have a vaccine, you may feel a bit sick. This can be some pain at the site of the vaccine injection, headache, tiredness or a fever. These side effects are not serious and should clear within a few days. You feel these side effects because your immune system is working hard in response to the vaccine.

There are also rare cases where some people have a more significant side effect to a vaccine. These serious reactions are very uncommon. For example, an allergic reaction only happens in approximately 1 in 1 million people.

Are vaccines safe for people living with cardiovascular disease?

Yes, vaccines are safe for people living with CVD. There is no evidence to suggest that vaccines are any less safe for people living with CVD, or that they have any more chance of experiencing side effects. However, there is very clear evidence that people living with CVD are more likely to become very sick from an infection. So the key takeaway for people living with CVD is that the risk of not having a vaccine, and becoming very ill from a respiratory infection, is much greater than your risk of having a side-effect from a vaccine. If you have specific concerns about your health and how vaccines may be for you, you should discuss these with your GP.

Do vaccines cause cardiovascular disease?

Neither the influenza or RSV vaccines increase your risk of heart events such as heart attack or stroke.

In very rare instances some types of COVID-19 vaccine may cause inflammation of the heart (myocarditis of pericarditis). This has been mainly reported in men under the age of 40, with most cases being mild and self-resolving. This risk, though, is much less than the risk of developing a serious heart complication from a COVID-19 infection. For context, it is estimated that your chance of developing heart inflammation is three times greater after a COVID-19 vaccine, but 18 times greater after a COVID-19 infection.

Where do I find good vaccine information?

There is a lot of information available online about vaccines and your heart that can be confusing and contradictory. It is always best to look to trusted sources of information when you have questions. These include places like the Department of Health in your state or territory, and large health information services like healthdirect.gov.au. Also, remember that the best place to go for information about your own personal health is your GP.

Are there any other ways to reduce the risks of CVD from respiratory infections?

Antiviral medicines are available that can treat flu infections, but how they impact your risk of CVD is unclear. Results from clinical trials have been contradictory, with some trials showing an improvement in CVD risk, and others showing it worsening, while others show no change. Looking after your heart by keeping active, eating a heart-healthy diet, reducing alcohol intake, and quitting smoking, can all help reduce your risk of developing CVD. Making these heart-healthy lifestyle changes in addition to having a vaccine can give you the best chance of reducing your risk of developing CVD from an infection.

Living well with a respiratory infection and cardiovascular disease

If you have a respiratory infection, there are lots of things you can do to feel better and help yourself recover. If you also have (or are at risk of developing) a heart condition, there are some additional things to consider:

Fluid intake

Advice for a respiratory infection is usually to increase the amount of water you consume. But, if you have a heart condition, such as heart failure, having too much fluid can cause strain on your heart. Speak to your GP or healthcare team to work out how much fluid is right for you to have.

Cold and flu medicines

These are available over-the-counter at your pharmacy and help ease cold and flu symptoms. Some of them can interfere with heart medicines though, so before you buy any make sure to tell your pharmacist what other medicines you are taking so they can check if they are safe for you.

References

- Interim Australian Centre for Disease Control. Australian Respiratory Surveillance Report. www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/2025-10/australian-respiratory-surveillance-report-6-october-to-19-october-2025.pdf

- Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI). Australian Immunisation Handbook. Available at: immunisationhand book.health.gov.au/.

- Kawai K, Muhere CF, Lemos EV, Francis JM. viral infections and risk of cardiovascular disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2025;14(21):e042670.

- Davidson JA, Banerjee A, Smeeth L, et al. Risk of acute respiratory infection and acute cardiovascular events following acute respiratory infection among adults with increased cardiovascular risk in England between 2008 and 2018: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. Lancet Digit Health. 2021;3(12):e773–e783.

- Sampri A, Shi W, Bolton T, et al. Vascular and inflammatory diseases after COVID-19 infection and vaccination in children and young people in England: a retrospective, population-based cohort study using linked electronic health records. Lancet Child Adolesc Health 2025;9(12):837–847.

- Davidson JA, Warren-Gash C. Cardiovascular complications of acute respiratory infections: current research and future directions. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. 2019;17(12):939–942.

- Kwong JC, Schwartz KL, Campitelli MA, et al. Acute myocardial infarction after laboratory-confirmed influenza infection. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):345–353.

- Smeeth L, Thomas SL, Hall AJ, et al. Risk of myocardial infarction and stroke after acute infection or vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(25):2611–8.

- Nguyen TQ, Vlasenko D, Shetty AN, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of respiratory viral triggers for acute myocardial infarction and stroke. Cardiovascular Research. 2025;121(9):1330–1344.

- Penders Y, Falsey AR, Bhatt DL, et al. Burden and severity of respiratory syncytial virus infection in adults with cardiovascular diseases: A systematic literature review. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2025;92:130–143.

- Harris E. COVID-19 vaccination linked with lower risk of cardiac problems. JAMA. 2024;331(17):1439.

- Xu Y, Li H, Santosa A, et al. Cardiovascular events following coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in adults: a nationwide Swedish study. Eur Heart J. 2025;46(2):147–157.

- Arunachalam S, Anuforo A, Hetekides S, et al. Real-world cardiorespiratory impact of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccination in the USA: a retrospective propensity-matched analysis. Circulation. 2025;152(S2).

- Buoninfante A, Andeweg A, Genov G, et al. Myocarditis associated with COVID-19 vaccination. npj Vaccines. 2024;9:122.

You might also be interested in...

.jpg?width=560&height=auto&format=pjpg&auto=webp)

How your heart works

Your heart is a muscle that pumps blood and oxygen to all parts of your body. Your heart also has its own blood supply

Time to book a Heart Health Check?

A Heart Health Check with your GP will help you understand your risk of having a heart attack or stroke in the next 5 years and what you can do to prevent it.

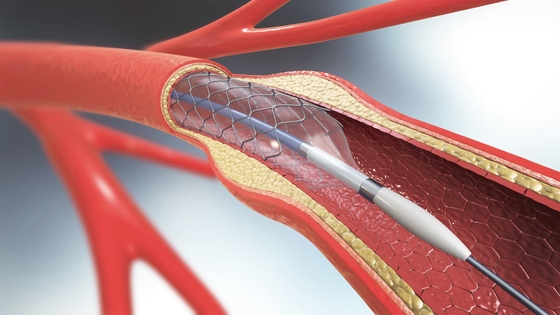

Heart procedures and devices

If you have a heart condition, your doctor may recommend different treatments, including procedures or devices.

Last updated07 December 2025