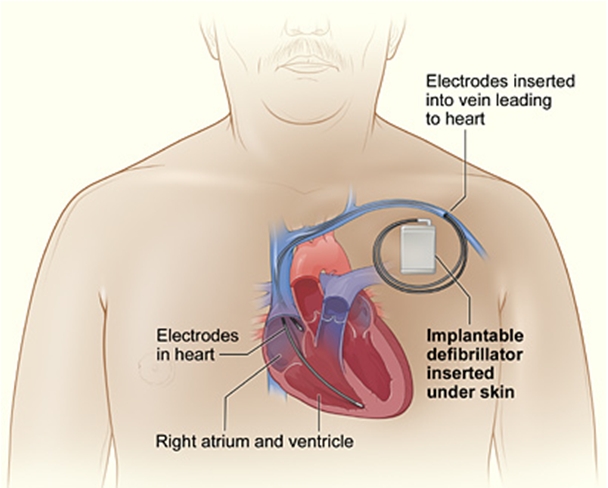

Automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD or AICD)

This is a device inserted into your chest to return abnormal heart rhythms to normal using electrical impulses.

Key takeaways

2 min read

An automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD or AICD) uses electrical impulses to return your heart rhythm to a normal pattern.

People who are elderly, have an inherited condition, have developed heart disease, or have a problem with their heart are candidates for having an ICD fitted.

Living with an ICD requires regular monitoring by your doctor to check the ICD settings and battery life, and the condition of your heart.

What is an automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD or AICD)?

An automated implantable defibrillator (ICD or AICD) is a device inserted into the chest to help fix fast, abnormal heart rhythms. These irregular heart patterns are called arrythmia. Your heart rhythm is the electrical signal that makes the heart beat.

Using electrical impulses, the ICD sends messages to the heart to slow down the fast rhythm and return to normal. If this doesn’t work, the ICD will send an electric shock to jolt the heart out of its dangerous rhythm.

ICDs have two parts: the ICD generator box, and the leads. The device sits under the skin on the left or right side of your chest.

Why do I need an ICD?

A healthy heart has a steady, regular electrical rhythm. However, in some people, this rhythm can become disrupted and make the heart beat too fast or too slow. This condition is called arrhythmia.

A person can develop arrhythmia as a result of:

Ageing

Inherited or genetic causes

Coronary heart disease

A previous heart attack

Heart muscle or heart valve problems

Heart failure or problems with your heart’s structure or ‘electrical system’.

If you’ve had a fast, dangerous arrhythmia before that made you collapse, or are at risk of having certain dangerous arrythmias, your doctor might recommend an ICD.

The benefits of an ICD

An ICD checks your heart rhythm 24 hours a day. If it detects an abnormal heartbeat, the ICD will attempt to bring your heart rate back to normal. It is an important device that could save your life.

How to prepare for the operation

Before having your ICD put in, you’ll need to:

Ask your doctor if you are able to take your usual medications, such as diabetes medications and blood thinners

Plan your transport home – you'll need to find someone who can collect you and help you get home when it's time to leave the hospital

Pack some essential items for an overnight stay (such as slippers, pyjamas, toiletries)

Shower using a special surgical wash that your doctor will recommend for you and explain how and when to use before your procedure

Not eat or drink anything before your surgery – your doctor will tell you how long before the operation you need to fast

Remove any jewellery.

During the operation

The operation to insert an ICD happens in an operating theatre. It usually takes one to three hours.

Before it begins, hospital staff will attach you to heart monitors and insert a type of tube called a cannula into a vein in your arm. Medications and fluids can be given through the cannula.

Once the surgery begins, your doctor will:

Give you a local anaesthetic to reduce the feeling in your collarbone area

Make a small cut near your collarbone that creates a pocket under the skin for the ICD to go in

Thread the ICD leads inside a large vein on the right side of your heart

Fix the end of the leads into position inside the heart using tiny screws

Program the ICD and do some tests to make sure it is working properly

Tuck the ICD device inside the pocket under the skin

Close the incision using stitches and apply a dressing to the area.

Additional leads may be inserted with your ICD depending on your doctor’s assessment of your condition. If you have congestive heart failure, a bi-ventricular ICD may be recommended.

After the operation

After your procedure, hospital staff will take you to the recovery area. You’ll have a special dressing over the area that was cut. It’s important you don’t change this until someone tells you. Your doctor will give you specific instructions for managing the wound. This area might feel sore, and there could be some bruising, but this should go away after a few weeks.

You will also be given information about the activities you can and can’t do while you are recovering from your operation. This could include things like not wearing clothes that will put pressure on your wound, and not lifting anything heavy.

Living with an ICD

After your ICD has been inserted, you will be able to see a slight bulge under the skin.

You’ll need to go to an ICD clinic for regular follow-up appointments. Your medical team will give you the contact information before you leave hospital.

What is a device check?

It is important to check the electrical function of your heart, your ICD’s settings, and its battery life. These checks do not require surgery. If the check is done in a clinic, the doctor will put a wireless wand on top of your skin to do this. Some newer ICDs have remote monitoring capability, which lets your doctor check your ICD while you are at home.

How long does the battery last?

The battery life of an ICD is five to 15 years. Your doctor will let you know how many years the battery has left at your device checks. Don’t worry, your doctor will not wait for the battery to be completely used up before changing it. A battery change is a quicker procedure than inserting an ICD.

I’m feeling down and worried about living with an ICD

Living with an ICD can be stressful. Many people worry about their device, getting shocked, and how their life has changed. It is OK to feel this way. Talk to your health care team and your loved ones about how you are feeling. Ask questions that help you understand your device and what it means in your life. With time, information and support, most people do become comfortable about living with an ICD.

If you find yourself feeling down or worried most of the time over a two-week period, see your GP. You may need some extra support.

What do I have to do differently, now that I have an ICD?

Things to know about when you are living with an ICD:

Make an action plan with your heart doctor about what to do if you get an electric shock from your ICD

Contact your doctor if you hear a beeping sound from your ICD – this suggests that the settings need to be checked

Go to your ICD checks

Make sure that all health professionals you see know that you have an ICD, in case you need specific care or instructions. This includes dentists and people giving you medical tests – for an MRI, let staff know that you have an ICD before you get to the appointment

Carry your ID card with your ICD details in your wallet or purse – take a photo of it and leave it with a family member

As a general precaution, try not to carry your mobile phone in your shirt pocket or place it very close to your ICD

When travelling, tell airport security you have an ICD, as it will probably cause the security scanners to beep – they will use a manual wand to check you.

If you are working and your job involves welding or electricity generators, talk to your doctor. Commercial drivers and people who operate heavy machinery should discuss the impact of an ICD on their work life.

Most sports and activities shouldn’t be a problem with an ICD, but it is a good idea to talk about them with your doctor, especially for high contact sports. An ICD should not interfere with your sex life.

When do I ask for urgent help?

Always call your doctor if you experience any of the following:

Numbness or tingling in your arm closest to your ICD

Loss of consciousness, either on its own or before feeling a shock

A beeping noise coming from your ICD

Signs of infection where your ICD was implanted, such as redness, swelling, warmth, bleeding or leaking fluid

Signs of a fever up to eight weeks after your ICD has been inserted

If you experience a shock, your doctor will tell you what to do. They may wish to be contacted immediately or only if you receive more than one shock in a one- or two-day period. Write down their instructions and keep this note or action plan close to you.

What happens if I am touching someone when I receive a shock from my ICD?

If your ICD delivers a shock, it will be inside your heart. There is no risk of transferring the shock to someone else.

ICDs and planning for end-of-life care

In the last stages of life, people can experience shocks more often from their ICD and this may prolong their symptoms of dying. This can be distressing for some people. You may wish to talk to your health care team and loved ones about when you would want to turn the shock function off. It is best to record your wishes about your ICD in an Advanced Care Directive.

For more information about a permanent pacemaker procedure, speak to your doctor, nurse or health worker.

You might also be interested in...

Heart procedures and devices

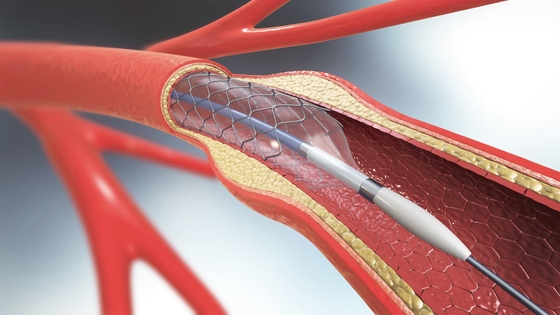

If you have a heart condition, your doctor may recommend different treatments, including procedures or devices.

Permanent Pacemaker (PPM)

A permanent pacemaker (PPM) is a small device that is inserted under the skin of your chest to help the heart beat in a regular rhythm.

New research to better control and treat life-threatening heart rhythm disorders

New research funded by the Heart Foundation aims to boost surgery success rates for life-threatening heart rhythm disorders (arrhythmias), leading to fewer Australians needing defibrillators installed in their chests.

Last updated18 February 2021